One great aspect of coin collecting is to just sit and ponder about what an old coin was used for when it was in circulation. To me it often more interesting than owning a coin. Of course, it is a little more than pondering. It inspires me to read about history, economy, travel or literature. Sometimes a coin inspires me to read about random loosely connected things for days, one after another. Or, it works the other way around, when I read a book that has currency mentioned I often go out and try to find the coins in question. This is of course, not an original idea. One example is Gerald Tebben’s Coin World article, What did Scrooge use to pay Bob Cratchit?, or the The Fourth Garrideb Club, which studies the coins used in Sherlock Holmes stories.

I am not even trying to compete with that kind of a research, but I found over the years that I was always excited to find old references to currency to understand how money was used and what it was worth. Of course, it only makes sense if it can be established that the information is valid. Partly this is why I mostly rely on travel books, because the money related data will be as valid as anything else, it is only about the credibility of the author.

One of my favorite authors, the Hungarian Gabor Molnar, in Hungarian his name is Molnär Gäbor, who spent two years in Brazil from 1930-1932. He makes tens of references in his books about the money he spent during his trip. It is such a treasure chest for coin collectors to get a sense of how some of these coins were spent. Actually, as I investigated it further, he more likely spent paper currency and not many coins. But let’s see what was his money worth and spent for.

About Gabor Molnar

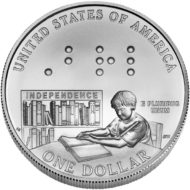

I Previously wrote about him in connection with my trip to Brazil last year. It is not over exaggeration to say that I learned to read from his book, which was 14 braille volumes. I was about 8 years old when I read it, by the time I finished the book I could read fluently. The first book I read was the adventures in the Brazilian wilderness. I am not quoting the title, as I could not find an English version of the book, most likely it wasn’t translated to English. The Hungarian title is: “Kalandok a brazíliai őserdőben ” (1940). When I traveled to Brazil, I managed to get the Portuguese translation of the book, “Aventuras na Mata Amazonica” (1973). It is probably not an accident that I later learned Portuguese, unconsciously this book must have been another inspiration.

Later I read another one of his books, “Éjbe zuhant évek” (1973), which roughly translates to “The night fallen on the years”. From this book I found out that he had to return from Brazil because of an accident, as he was trying to dispose of a pack of dynamites, he stumbled, fell and the package blew up. He lost his eye-sight immediately. After returning to Hungary, he learned to use the typewriter, and for practice he wrote about his adventures. A friend of his noticed it, and less than a year after his return, one of his stories was published. The rest is history. He was one of the most popular Hungarian authors of the century. He wrote about 26 books mostly about Brazil, and three about Mongolia based on three visits in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

Gabor Molnar traveled to Brazil to collect bugs, butterflies, animal skins and other items to send to the Hungarian National Museum. He left with two other people, who became ill and had to return before they could even start their work. He has greatly impacted my life with his example. What he started doing in the 1930’s as a blind person, was very unusual at the time. All he had was a typewriter, some people he paid to read to him, and later a tape recorder that allowed him to take notes and listen to audio books.

As I have read all of his books and articles I could find, I could write about him much longer, but let’s turn to Brazil now and talk about the currency of the time.

Money in Brazil in 1930

First let’s see what was money like in Brazil when Gabor Molnar arrived. The currency at the time, since 1799 was the Brazilian Real, until 1942. The currency went through several transformations, partly due to the changing economy and inflation. In 1930, the money was called mil réis, because most things cost over a thousand reis, while smaller coins were still in circulation, mostly larger denomination banknotes were used. Gabor Molnar always refers to money as mil reis, and not Reis. In the Hungarian edition he spells it as “milreisz”, according to Hungarian pronunciation, but the Portuguese translation has the original spelling, mil Réis.

In 1926 the Reis was pegged to gold at 180 MG to 1000 Reis. In the meantime, the US Dollar was pegged to the gold at the rate of $20.67 an ounce. What this amounts to is an ounce of gold was 172.8 Brazilian mil reis. Thus, 1 USD was approximately 8.35 mil Reis at the time. However, Gabor Molnar consistently converts the USD to 12000 mil Reis. It has to be noted though that he has not used Dollars during his trip, for all practical purposes he had to convert to and from Pengo which was the currency of Hungary at the time. He also mentions using Swiss Francs, but all Dollar values are for calculation purposes and not exchange rates.

In 1933 the Reis was pegged to the USD at the rate of 12500 Reis = 1 USD, which approximately corresponds to Gabor Molnar’s calculation of the Dollar. It is possible that at the time of writing in 1940, he looked at the 1933 Brazilian Reis prices, but by that time it was pegged to the Dollar and not to gold. At this point the Reis/USD conversion rate was much easier, though I was not able to find any actual conversion tables from those years, this is why I had to calculate using the price of gold.

The price of goods and services in mil Reis

In the following, I will only use mil reis as found in the book. So, let’s dive in, and see what Gabor Molnar paid during his trip.

He left Hungary at the end of May, 1930, and arrived to Recife in early June. They got a hotel room for 15 mil Reis, full room and board.

From Recife, he had to travel to Manaus alone, as the other two members of the expedition became ill. On the way he saw many sharks and mentioned that there was a shareholder company, which caught and processed sharks. The company was established with 2 million mil Reis, in the Portuguese translation this amount appears as dos contos de reis. A conto Reis in Brazilian Portuguese means a million Reis.

When arriving to Manaus, he only had 240 mil Reis, here he gives a probably wrong conversion, 20 USD.

In Manaus he bought a hat and film for his camera for 30 mil Reis. Though he doesn’t say how much film he bought, we can only assume that it was more expensive compared to other goods than what it would be today.

As he was walking around, he found a few places where they were roasting meat over coal. When he asked about the cost of a bag of coal, which looked like it was at least 30 Kilos. The price was only 6 mil Reis. Which is about the daily pay of a hoarder/manual worker, 5-6 mil Reis. It does not make an easy living, and yet it is quite a bit of work.

He bought a local paper, hoping that this is the fastest way to learn the language. He must have been onto something, in less than 2 years he learned Portuguese fluently. Actually much sooner, because most of the time he was already using the language. For that matter, Gabor Molnar was who later published the first Hungarian – Portuguese dictionary in 1948.

In the newspaper he found that they pay 12000 mil Reis for a prepared jaguar skin. According to him, they don’t pay much to the Brazilian hunters. It is hard to verify, as I have no idea what it takes to find, shoot, skin and prepare a jaguar, but it is valued at two days work of a hoarder. Later on the boat he saw somebody selling a jaguar skin for this price.

He met a woman who just returned from Belem to Manaus by boat. The trip is 6 days for 60 mil reis, which also includes food.

When a boat stops, traders get on it to sell all kinds of things, he bought two painted dishes for 1 mil reis.

Llater he was running out of money, he had to look for cheaper rooms, this time one with hooks for a hammock for only 3 mil Reis a night.

As he started collecting bugs and butterflies, he mails five boxes of unknown size to Hungary, to the National Museum for 10 mil Reis and 800 Reis. This is how he gives the price, not 10800 Reis.

Later he invited two friends to watch a movie, for almost 100 mil Reis. That is, for more than 6 days of room and board in the earlier hotel. By this time he managed to sell some stuff and make money.

Once he went into a store to buy a gun. The cost was 60 mil Reis, but when he was hesitant to buy it, the owner gave it to him for a few days to try with a dozen of bullets in exchange for his passport. He got some free use out of it, because when he returned he ended up buying another gun for 50 mil Reis which also came with two boxes of bullets.

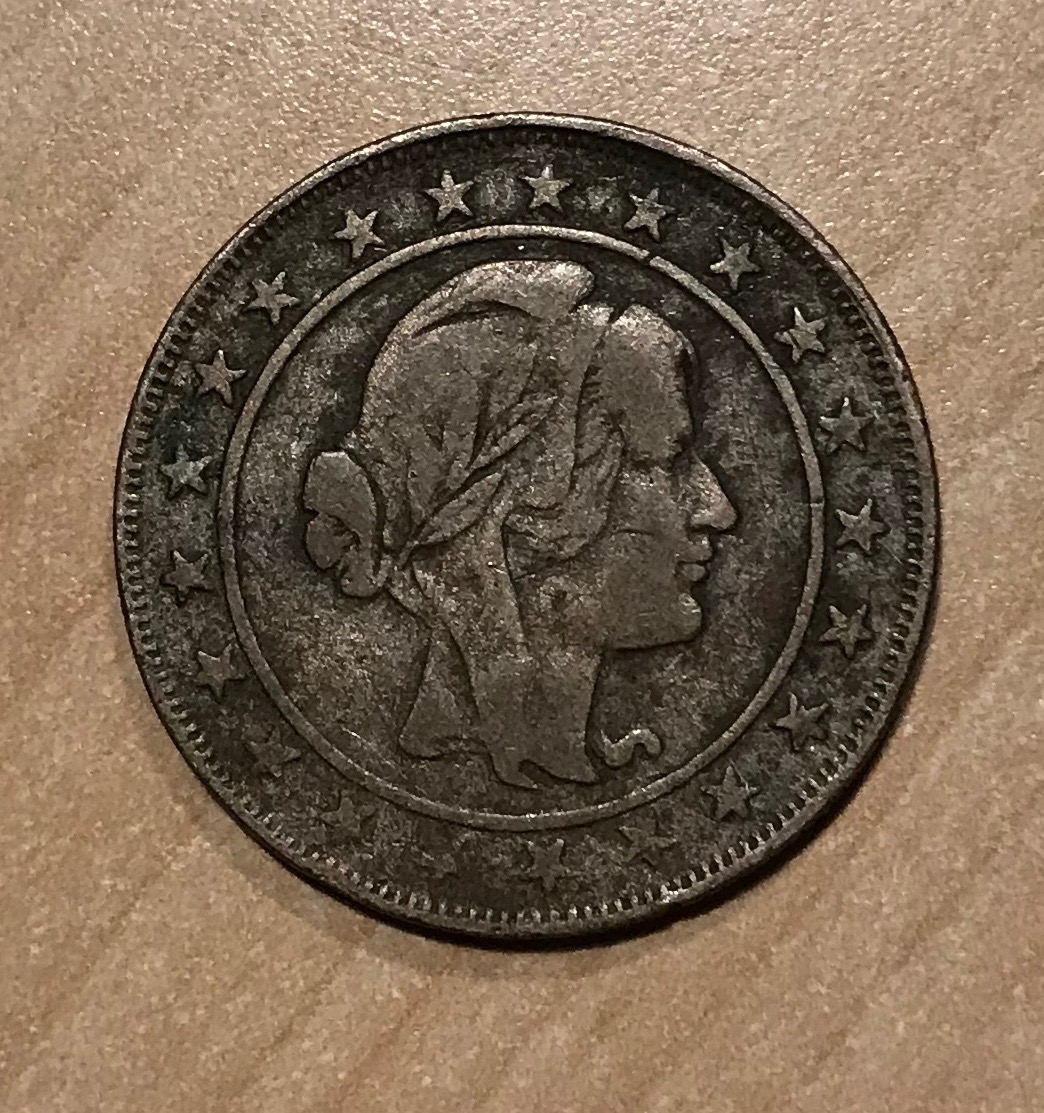

< img src="/image/brazil-1929-2000-reis-reverse.JPG" alt="2000 reis reverse 1929">

One of the more interesting expenses was when people around him found out that he was collecting bugs, somebody came to him with 3 huge, 12 centimeter long bugs. He immediately gave a tip of a silver 2000 mil Reis.

Most likely it was a huge tip, because it was so exciting that from then on people were collecting all kinds of bugs for him in hopes for a similarly generous tip. The following day they people brought 5 boxes of half dead broken bugs and butterflies to him. This time he was only gave a mil Reis, but there was no dissatisfaction.

On one of the first hunting days he hired a few leaders for 3 mil Reis a day. Interesting that this is only half of the wages a hoarder gets, for probably for much better skills.

Moving on from Manaus to Boa-Vista, an 8 day boat trip was 108 mil reis on first class, and 36 mil reis on third class. All including food.

In Boa-Vista he received a job offer at a plantation to be an agronomist, for 600 mil reis a month.

The last price from the book is a giant turtle for a half mil reis. In other parts of the world it would be much more expensive, but here they are only buying it for the meat.

The majority of the book doesn’t contain more interesting prices, as Gabor Molnar spent most of his time hunting and collecting. The above amounts were spent in a few months only out of the 1.5 years the book covers.

The second book starts before the Christmas of 1931 and finishes in April, 1932 when he arrived back to Hungary after losing his eye-sight.

At this point he was working at the Fordlandia plantation as an agronomist but spent most of his time hunting and collecting. Though he is only getting paid when he is working, he still believed that the daily 28 mil reis was a good salary. He was more interested in the adventures than the work itself.

The property of Fordlandia, Companhia Ford Industrial do Brasil bought its property from the father of one of his friends, for 30000 mil reis. We don’t know the size of the property, only that thousands of people were working there.

He received another offer for a monthly 800 mil reis to another plantation, where he would not be able to spend that much time in the wilderness, so he refused it for the sake of adventures.

He called his salary the ticket to freedom in the shape of 100 and 200 mil reis banknotes.

For the adventures, he hired three extremely skilled leaders/hunters, for the above mentioned 3 mil Reis.

He sent home two of the largest bugs of the world, the Titanus giganteus, and sold one for 80 Dollars. This is the only price he mentions in his book in USD.

After he lost his vision, he received 7000 mil Reis from the insurance company, just a bit less than his salary for 1 year of work. This money was enough to cover his trip back to Hungary and the shipping costs of the three anacondas he brought back to the Hungarian Zoo. He only had some money left for the first few days in Hungary. On the way home he met a German traveler who received 3500 mil Reis from the insurance company for losing one of his eyes. Interesting that the compensation seems to be per eye, and not the changed circumstances. It is much harder to continue life with one eye than without any eye-sight.

On the way home they had to stop in Belem and stayed in a room for two with his guide, for 8000 mil Reis with only hooks for the hammocks. He was traveling with a Hungarian guide for a while, who didn’t refuse a drink when he got one. He asked for 100 mil Reis for his expenses, but drank it up in one night. Almost two week’s worth of the room expense.

The last stop in Brazil was in Recife, where he paid 200 mil Reis to transfer the three boxes with the snakes on the next boat. Though it was two years later, and an international port, it is much more than the 6 mil Reis of the hoarders daily wages. But there was an accident, and a snake bit one of the hoarders, He offered another 100 mil Reis for the doctor, but the hoarder said he will keep the money and won’t spend half of it on the doctor. Interesting, probably hoarders were making more than doctors in Recife.

And the last expense, when he arrived to Hungary, from the train station he wanted to go to the Zoo to deliver the snakes. However, he didn’t have any local currency. He gave 50 mil Reis to a hoarder to put the boxes into a taxi. He assured him that it was worth 19 Pengos. For comparison, less than a year later, for his first articles in a newspaper he got 12 Pengos, and spent 90 Pengos a month for a rental room with meals.

These numbers are by no means indicative of what life was like in Brazil in the 1930’s, or what it cost to live there. It is a huge country, and as we could see already, different places had different prices. Also, the prices quoted are not necessarily related to the everyday type of expenses. However, without being thorough, these prices can give us a small slice of what it cost to travel in Brazil in the early 1930’s.